I’m thinking about some words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian who would be 100 this year: “I should like to speak of God not on the boundaries but at the center, not in weakness but in strength.… God is beyond in the midst of life.” It comes from Letters and Papers from Prison, written in the years before his death at the hands of the Gestapo. By my reckoning, Bonhoeffer’s death in 1945 at 39 was untimely. It was also confusing: it left most of his ideas without sufficient elaboration and me, like many, pondering the insights of his realistic, kindred, searching spirit. And so I ask here, What does God “at the center” look like?

Did I see it one December in New York City when I trekked with my family to Radio City Music Hall? There we sat, enchanted by the world-famous Rockettes. There we watched the Christmas Spectacular—set that season to entertain its fifty millionth customer right at Rockefeller Center, right in Midtown Manhattan, certainly a great cultural and financial center. And there we heard the Gospel.

The Christmas Spectacular pulls out every theatrical and technological stop. Through video, we ride with Santa on his sleigh through New York City. We watch a lovely pair of skaters suddenly appear on an ice rink that gradually rises before the astonished audience. We view the orchestra disappearing from the front of the stage only to re-emerge behind the synchronized Rockettes.

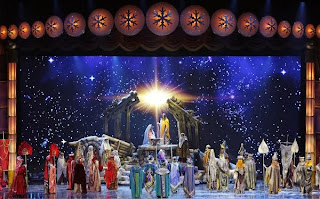

In one sense, this is simply Broadway theatrics. But I wasn’t prepared for the finale of the Christmas Spectacular, the point to which the entire show was leading. The show slows and becomes more patient at its end as it presents Jesus’ birth. Naturally, live manger animals fill the stage. They surround Jesus and a stunningly beautiful Mary, attended by a handsome Joseph. But the hype has significantly quelled when, on the enormous video screen, “One Solitary Life” scrolls down.

It begins,

He was born in an obscure village, the child of a peasant woman.He grew up in another obscure village,where he worked in a carpenter shop until he was thirty.

And ends,

All the armies that ever marched,and all the navies that ever sailed,and all the parliaments that ever sat,and all the kings that ever reigned put togetherhave not affected the life of manupon this earth as powerfully as this “One Solitary Life.”

This is not a Times Square evangelist in a faded and tattered tweed jacket on a wooden box, shouting “God is ready to judge the world.” No, here the Coming of God in Jesus is proclaimed through fabulous costumes, spectacular sets, and fifty dancers in perfect synchronization.

I had to pause after the show and reflect: Did this dazzling display of technology serve the Gospel? Some doubt that it’s possible since technology is a greedy servant, either demanding allegiance from its master, or more often becoming the lord itself. Along these lines, I spent a couple of days in Missoula a few years ago at the University of Montana in a consultation with the contemporary philosopher of technology—and Christian—Albert Borgmann. Borgmann expresses significant concerns about the power of technology and the “device paradigm.” Do we want dinner? Nuke some prefab, individualized portion in the microwave. Want to be entertained? Turn on the tube. Want to exercise? Jump on a Stairmaster. Technology seduces with the dazzling power of manipulating our environment. To put it at the service of the Gospel is oxymoronic at best. Borgmann offers instead habits that focus us on real life, “focal practices,” such as preparing a meal together, talking as a family over dinner, and jogging through nature.

The Bible also expresses an uneasiness about worldly power in the service of the message of Jesus. Paul clearly spoke of God’s power in weakness to the power-happy people of cosmopolitan Corinth. And what Christian can be totally serene about the joining of the Rome and Christianity by Constantine, an emperor who saw a vision of the cross over sun with the words “in this sign you will conquer”? Following a Messiah—unjustly crucified by the duly installed powers of religious and political justice—does not make an easy marriage with earthly powers of any sort. In fact, the Nazis hanged Bonhoeffer because his active resistant to their demonic political regime led him to collaborate in an assassination attempt on Hitler. Bonhoeffer would certainly hesitate to call Broadway glitz prophetic. (Sometimes it’s actually more pathetic.)

Still—and I say it guardedly—I glimpsed something in the Rockettes as they brought God’s coming in Christ to the center. I was reminded that God is the Lord not only in weakness, but also in strength. And since God gave us the mandate to exercise dominion in Genesis 1, we have a clear call to change our environment for the good, and thus a call to use technology. In fact, I have found it tough for many to imagine God in strength at the Center—to bring God into the moments of the heights, the moments when joy overwhelms our attentiveness to the Spirit, when bodily pleasures of food, or music, or sex overwhelm and mute our prayers, when we develop some new technological wonder and we hear Satan’s alluring words to “become like God.” In these moments, Bonhoeffer—and the Rockettes—lead us to the simple truth: God is there, in strength, in technological discovery, at the center.

Clearly the Christmas Spectacular is not the whole story, and no one should portray it that way. If there’s anything clear about Jesus’ message, it comes first to the lowly and the marginal, not those who can afford $75 tickets. At the same time, it would be criminal for Christians—with theatrical tools at their disposal—not to use them at the service of the Gospel. (I, for one, think that Christmas cartoons are richer and truer to the message because Charles Schulz insisted that Linus read Luke 2 in A Charley Brown Christmas.) Sure, there are inevitable distortions that this project can bring to the Gospel, to bringing God to the centers of power. And yet, there are inevitable distortions to leaving God only at the margins—in second-rate theatre, for example—because God fills every part of creation.

Bonhoeffer, Rockettes, and the Gospel—perfect together? Perhaps not. But at least compatible. They’re even connected by the God who came, yes, in the weakness of a baby, but who is not too proud to be displayed in the dazzling power of theatrical technology.