If understand it correctly, a standard argument goes like: Postmodernism declares that “nothing is absolute,” but since that statement constitutes an absolute, postmodernism is self-contradictory and therefore absurd. Postmodernism has therefore nothing to offer. I don’t actually think that’s what “postmodernism” says—as I read contemporary authors, they state in a much more limited way, that they simply can’t find any absolute statements that hold up and that the path to certainty is strewn with road-kill. So I strain out a slightly different insight: there is a latent inconsistency, the Postmodern Paradox, in our contemporary philosophical and cultural climate. We want a grand narrative, but distrust it. So our Big Story is that there is none.

You see, I’m as distrustful of totalizing concepts as the next guy. I can sniff them out even when the author protests against them. So what I take up here—with Nicholas Taleb’s The Black Swan to my right—is that his contention that we by nature create huge structures in order to assert certainty and predictability in a highly improbable world. He calls this tendency (among other things): PLATONICITY, “our tendency to mistake the map for the territory, to focus on pure and well-defined ‘forms,’ whether objects, like triangles, or social notions, like utopias… [etc.].” But we don’t live in the world of the Forms. (Actually Plato didn’t think we did either.) Taleb wants to open us to the possibility of the Black Swan, to events and realities we could never predict, but that constitute what is most definitive for our lives and our world. Who could have seen the stock market crash of 1987 or the planes of 9-11? In other words, Black Swans rule, in a world that can only countenance boring, predictable white swans.

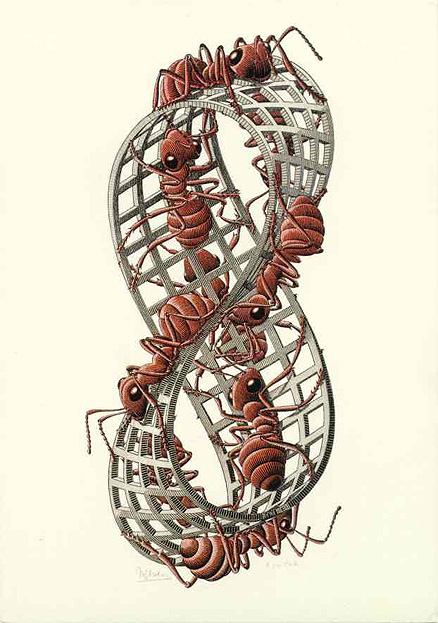

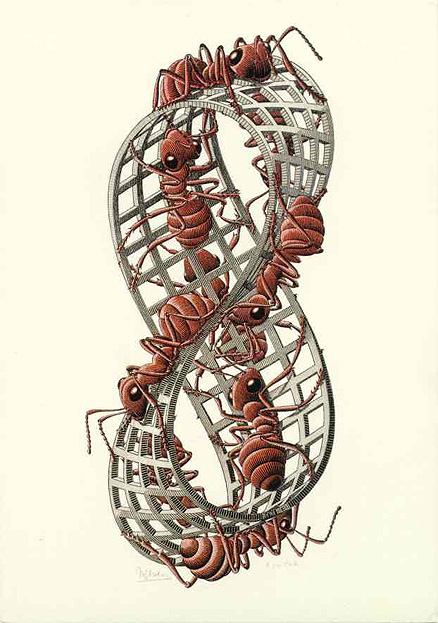

So I come to the Postmodern Paradox: No sooner does a thinker like Taleb want to emphasize the fragmentary, the irrational, the postmodern—no sooner does he evoke an incredulity toward metanarratives—than some new meta-structure comes around the back door. The Black Swan constitutes his totalizing structure. (The definition is in the post below.) Taleb wants to eschew the certainty that we derive from perfect, platonic concepts. And yet, it comes around that famous one-sided Mobius strip. In an odd way, it seems, asserting unpredictability (against the common, pedestrian desire for the known and the repeated) offers Taleb some level of mastery over the world. And that, to be sure, is a paradox.