Last week, I mentioned that I’m teaching a class on C. S. Lewis. Well, I’m still teaching

the class, and this week I’m pondering Lewis’s famous conversion to Christianity. (Or perhaps, since he grew up with Christian teaching, return to faith.) I’m particularly intrigued by two elements—what confessing Jesus as the Truth meant to him in light of the scientific mindset of his day and how imagination, not simply rationality, brought Lewis to this conclusion.

|

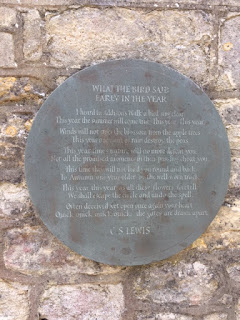

| Addison's Walk, Magdalen College, Oxford |

Jesus as the “True Myth”

First of all, let me cite St. Clive’s famous letter to his childhood friend, Arthur Greeves, after the walk he took with Dyson and Tolkien on Addison's Walk in Oxford in September 1931.

A pair of significant excerpts:

“I have just passed on from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ – in Christianity… My long night talk with Dyson and Tolkien had a good deal to do with it” And “Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the others are men’s myths.” (C.S. Lewis to his friend Arthur Greeves, October 1, 1931)

This is offensive because it makes an historical figure—hardly amenable to scientific proof, and bound to the culture in which Jesus lived, instead of the cross-cultural truths of science—at the center of what is true.

Erwin Schrödinger, Empirical Reality, Imagination, & Early 20th Century Science

It’s striking to me that Lewis used to walk around the same halls of Magdalen College where Erwin Schrödinger was from 1933-1938. I don’t know if they hung out, but it does signify that Lewis lived in an environment with top scientists.

And this brings me back to the question of the scientific thinking of his day. When he returned to faith in Christ as God, Lewis came to this conclusion based on imagination. When I referred to “science” in the previous post, I indicate with sufficient clarity that sciencenot only impliedrationality, but empiricism, that knowledge comes through the senses. And thus the materialism that accompanied much of early 20thcentury science.

And yet it was Schrödinger and others that gradually built an understanding of physical reality that went far beyond what we can grasp with our human senses… or really understand with our brain. To picture a quantum world with “quarks,” “spin,” and “charm” probably already indicates that we have moved beyond bare empiricism to a least a fair dose of imagination.

As Neils Bohr expertly phrased it:

“Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not understood a single word." And " If you think you can talk about quantum theory without feeling dizzy, you haven't understood the first thing about it.” Niels Bohr

In fact, we realize that so many elements of science—understanding the human genome, probing the nature of quantum reality—is way beyond human senses. The philosophy of science has moved beyond the Vienna School’s “verification” and even Karl Popper’s “falsification” to the saner and more accurate description by the late Oxford philosopher Peter Lipton, “inference to the best explanation."

Lewis’s Early “Imaginative Failure”

All in all, the pure empirical side of science has faded. But Lewis’s world hadn’t shifted entirely… at least, if thinkers proposed to be “scientific.” And so he had to move beyond those narrow boundaries and into the truth of imagination. As A. N. Wilson right notes what had restricted Lewis was an unwillingness to come to terms with life beyond empiricism.

“He stopped short of understanding Christianity because when he thought about that, he laid aside the receptive imagination with which he allowed himself to appreciate myth and became rigidly narrow and empiricist.” Thus, not to believe in Christ was for Lewis, “an imaginative failure.” A. N. Wilson

The Reconciliation of So Many Things

But that September night in 1931, St. Clive’s imagination was operating fully, inspired by a sudden—almost divine—wind as they walked, and the masterful imagination of Hugo Dyson and the maestro of myth, J.R.R. Tolkien. Indeed the reconciliation of rationality, empirical reality, and imagination—the truth of Jesus with the beauty of myths—all came together that fall night.

I’ll let CSL have the final word:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”